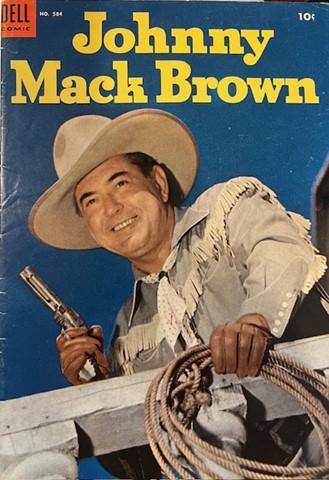

Crimson Tide head coach Wallace Wade on his star Johnny Mack Brown, Bama’s first Rose Bowl hero and future Western film icon

So uttered the words of 89-year-old Wallace Wade in reply to my question during our phone chat on Nov. 1, 1981.

“Coach, what did you think about Johnny Mack going into the movies?” I asked.

I expected words of praise and adulation, maybe even a few “attaboy” tributes to his star player from the 1923, 1924, and 1925 Bama squads, including, most notably, the 1926 Rose Bowl team. After all, for almost 40 years, Johnny Mack appeared in countless movies and television serials. Greta Garbo, Joan Crawford, Mary Pickford, Anita Louise, and Katharine Hepburn were but a few of his leading ladies. While at Paramount and Universal Studios, he worked with such legends as Mae West, Tex Ritter, Bud Abbott, Lou Costello, and John Wayne. He even appeared on an episode of “Perry Mason” in 1958.

Johnny Mack played dramatic roles early in his career, but gradually turned to the he-man Western roles that appealed to his athletic nature. He liked to ride, and as a law-enforcing gun hand, he came to be the No. 1 outlaw hunter. He was an elite horseman and handled many of his own stunts.

Johnny Mack also became an expert in fast draw and the handling of his six-shooters. Playing the lead role in “Billy the Kid,” he used a set of guns that had belonged to the real Billy the Kid. Another friend, Will Rogers, taught him how to lasso.

Johnny Mack, his wife Connie, and their four children were one of the finest and most popular families in Hollywood. Close friends included Fay Wray, Ginger Rogers, Ralph Bellamy, Spencer Tracy, and Douglas Fairbanks. He hunted with Clark Gable and swam and worked out with “Tarzan” star and Olympic gold medalist Johnny Weissmuller at the Hollywood Athletic Club.

In other words, Johnny Mack Brown was a big deal. A national Western film hero. A superb athlete. A member of the College Football Hall of Fame, class of 1957.

But when asked his opinion on Johnny Mack’s long movie career, Coach Wade’s answer was short, abrupt, and, frankly, took me by surprise.

“Well, he had to make a living somehow.”

I couldn’t help but chuckle at his response. In reality, though, coming from the tough, stern, hard-nosed, no-frills Wade, that answer should’ve been expected. To him, a career in the movies bordered on frivolity.

As Alabama returns to the Rose Bowl to battle Michigan on Monday, I think back to our storied tradition with the “Granddaddy of Them All,” especially the school’s first one on Jan. 1, 1926. The 20-19 comeback triumph over Washington solidified Alabama as the football power of the South. Historian Andrew Doyle dubbed the victory “the most significant event in Southern football history.”

Soaking in the stories of the 1926 Rose Bowl without mentioning Johnny Mack’s heroics would be akin to dissecting the intricacies of the wishbone offense without Johnny Musso. The jump pass without Harry Gilmer or Joe Namath. The Goal Line Stand without Barry Krauss. “The Kick” without Van Tiffin. “The Sack” without Cornelius Bennett and, bless his heart, Steve Beuerlein. Second & 26 without Tua Tagovailoa and DeVonta Smith. Fourth & 31 without Jalen Milroe and Isaiah Bond.

As many great games as Johnny Mack played during his days with the Tide, he saved his best for last. But getting to that point didn’t come easy.

Nicknamed the “Dothan Antelope” as a nod to his South Alabama hometown, Johnny Mack was a freshman on the Tide’s 1922 squad that shocked John Heisman’s Pennsylvania Quakers, 9-7, in Philadelphia. As a sophomore in 1923 (Wade’s first as head coach), the young, swift halfback showed tremendous potential, but rarely played.

“Why not?” I asked Coach Wade. His answer was firm.

“…because he wasn’t a very good blocker or tackler,” replied the Hall of Fame coach. “He was a great runner and a great pass receiver, but he was weak on defense. Until he became a good defensive player, we couldn’t afford to play him. We had to have an all-around football player.”

Johnny Mack’s defense, blocking, and tackling must’ve greatly improved, because his play flourished during the 1924 and 1925 seasons, culminating in his magical Rose Bowl performance.

After a five-day, 2,800-mile train ride (including a stop at the Grand Canyon and a workout in Williams, Arizona) and a week of practices and sightseeing in the Los Angeles area, the Tide was ready to prove wrong the West Coast writers, one of whom wrote, “The Purple Tornado (Washington) will have all its steam up to blow the Tide back across the continent as a pale pink stream.”

For the first half at least, Alabama appeared shaky. The Huskies, paced by their big running back George Wilson, vaulted to a 12-0 lead, but Johnny Mack and his Tide teammates quickly went to work to open the third quarter. The crowd of 45,000 was shocked to see Alabama score three straight touchdowns during a seven-minute span, then hang on for the 20-19 win. Johnny Mack scored two of those touchdown on long pass plays, one for 63 yards from Grant Gillis and another from Pooley Hubert for 30 yards. He was also the leading ground gainer that day, outdueling the Huskies’ Wilson.

In our phone conversation, Coach Wade recalled Johnny Mack’s valiant performance.

“We were one point ahead (20-19),” he said, “and on the last play of the game, this great big powerful runner they had (Wilson) broke loose for a long run. Johnny Mack was playing safety and Wilson was 8 to 10 yards beyond the line of scrimmage before he ran into Johnny Mack.

“Having had some questions in my mind about Johnny Mack’s defensive play in his earlier days, I thought to myself, ‘Well, there’s our football game.’ But he went in there and made as fine a tackle as you’ve ever seen. In spite of the fact that he caught two touchdown passes in that game, stopping that big bull to save the game for us was the thing that stood out most for me.”

Post-game praise for the Tide reigned throughout the nation. The Los Angeles Evening Herald wrote, “Tuscaloosa, Alabama, which Western fans didn’t know was on the map, is the abiding place of the Pacific Coast football championship today.”

Shortly after graduating in spring 1926, Johnny Mack married Cornelia Foster, daughter of Judge and Mrs. Henry Foster of Tuscaloosa. The pair had met at a Kappa Sigma fraternity Sunday brunch during his sophomore year.

“Johnny Mack was very handsome and a big hit with the girls,” Connie said in our phone conversation. “And he was quite a good dancer.”

After a very brief stint in the insurance business back in Dothan, Johnny Mack and Connie returned to Tuscaloosa. Serving as a Tide assistant coach during the 1926 season gave him the opportunity to coach Tolbert and Billy, two of his younger brothers.

Coaching his brothers, however, wasn’t the only bright spot for Johnny Mack during the 1926 season. Following Alabama’s return trip to the Rose Bowl, where they battled heavily favored Stanford to a 7-7 tie, Champ Pickens, Alabama alumnus, promoter, author, and later founder of the Blue-Gray All-Star football in Montgomery, and actor George Fawcett—who’d had his eye on Johnny Mack since the previous year’s Rose Bowl—took the young star under their wing and steered him toward the bright lights of Hollywood.

Johnny Mack never returned; he was an instant success on the silver screen.

After all, in the words of his coach, he had to make a living somehow.

© 2023 Tommy Ford All Rights Reserved